Spatial Memory Safety with Dependent Types in Codex

This tutorial was originally written by Julien Simonnet, Matthieu Lemerre and Mihaela Sighireanu in September 2024 to accompany the OOPLSA 2024 paper. You can find the original tutorial in PDF format, However, Codex's interface as evolved since then, and this HTML version will be kept up to date.

It provides a user guide for the static analysis based on the dependent nominal type system presented in the paper and implemented using Codex.

The analysis detects memory vulnerabilities (for example, null pointer dereferencing, out of bounds memory access, unsatisfiability of a memory invariant) in C or binary programs. For this, the analysis requires a specification of the correct memory layout of the program. This specification is given as a set of type definitions. The types used extend C types with specific constructs including type refinement by a predicate, unbounded unions or parameterized type definitions.

The analysis is inter-procedural, i.e., it could analyze functions separately. For this, the specification file may include function declarations (profile) using the type defined. In the following, we introduce the specification language for types, the options and out- puts of the analysis, as well as a usage methodology through several analysis examples. The full concrete syntax for type specification is given in Section A. The formal presentation of the analysis is given in the OOPLSA 2024 paper.

Getting started

First example in C

Consider the following C code. It has been extracted from the code of an OS where it was used to encode messages in an IPC (Inter-Processs Communication) mechanism. The code defines two record types representing a list of messages (message) and a message box (message_box) storing the head of a message list. The function zeros_buffer fills all the buffers in a message box with zeros.

struct message {

struct message *next;

char *buffer;

};

struct message_box {

int length;

struct message *first;

};

void zeros_buffer(struct message_box *box) {

struct message *first = box->first;

struct message *current = first;

int length = box->length;

do {

for (int i = 0; i < length; i++) {

current->buffer[i] = 0;

}

current = current->next;

} while (current != first);

}example.c: first example program.

To run our analysis on this example, we provide as input to codex the C code file example.c and a specification file example.typedc defining the correct memory layout. The simplest specification we could provide is given below; it is similar to the type definitions of the program, with one key difference: unlike in C types, Codex does not mix pointer types * and arrays. Thus we declare an explicit array of unknown length (len quantified existentially) to host our buffer. We also include the signature of the zeros_buffer function.

region buffer = ∃ len : int. (char[len])

struct message {

struct message* next;

buffer* buffer;

};

struct message_box {

int length;

struct message* first;

};

void zeros_buffer(struct message_box* box);example.typedc: simple type specification for example.c.

The specification language is described in more detail in Specification using Dependent Types, and its concrete syntax reference can be found in Type_parse_tree.

With this source code and type specification, we can now run codex on the provided files with the following command.

$ frama_c_codex -codex \

> -codex-use-type-domain -codex-type-file example.typedc \

> example.c -main zeros_buffer -machdep gcc_x86_32 \

> -codex-exp-dump -codex-output-prefix v0-

[kernel] Parsing example.c (with preprocessing)

[Codex_config] Setting pointer size to 32

...The passed options are:

-codexto activate the Codex extension in Frama-C;-codex-use-type-domainto trigger the type analysis, with-codex-type-file example.typedcto provide our type specificationexample.cthe C file to analyze, along with-main zeros_bufferto specify which function we want to analyze-machdep gcc_x86_32to specify the machine dependent architecture (32 bit machine)-codex-output-prefixto specify av0-prefix for output files. This is useful here to distinguish the mutliple runs we will do on our example.-codex-exp-dumpto specify that codex should output to a text file. An alternative HTML output is supported with-codex-html-dump. One file is created per function. The file naming scheme isprefix ^ funcname.cdump, thus, in our casev0-zeros_buffer.cdump

The analysis output can be seen in the dump file:

$ cat v0-zeros_buffer.cdump

example.c:12.26-36: `box->first' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

example.c:12.26-29: `box' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message_box*)

example.c:13.28-33: `first' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

example.c:15.15-26: `box->length' -> [--..--]

example.c:15.15-18: `box' -> ([1..0xFFFFFFFB] : struct message_box*)

example.c:18.20-30: `i < length' -> {0; 1}

example.c:18.20-21: `i' -> [0..0x7FFFFFFF]

example.c:18.24-30: `length' -> [--..--]

example.c:19.6-21: `current->buffer + i' -> [0..0x7FFFFFFE] or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : buffer[{0}].[0..0x7FFFFFFE]*)

example.c:19.6-21: `current->buffer' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : buffer*)

example.c:19.6-13: `current' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

example.c:19.22-23: `i' -> [0..0x7FFFFFFE]

example.c:18.32-35: `i + 1' -> [1..0x7FFFFFFF]

example.c:18.32-33: `i' -> [0..0x7FFFFFFE]

example.c:21.14-27: `current->next' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

example.c:21.14-21: `current' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

example.c:22.11-27: `current != first' -> {0; 1}

example.c:22.11-18: `current' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

example.c:22.22-27: `first' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

Unproved regular alarms:

example.c:12: Memory_access(box->first, read) {true;false}

example.c:19: Memory_access(current->buffer, read) {true;false}

example.c:19: Memory_access(*(current->buffer + i), write) {true;false}

example.c:21: Memory_access(current->next, read) {true;false}

Unproved additional alarms:

Proved 1/5 regular alarms

Unproved 4 regular alarms and 0 additional alarms.

Solved 0/0 user assertions, proved 0This dump file is organized as follows:

- The first part, before

Unproved regular alarms:, gives the abstract states computed by the analysis at each program point ofzeros_buffer. The meaning of these lines is explained in the next section. The second part starts with

Unproved regular alarms:and lists the potential memory vulnerabilities detected. For instance, the memory access done by the read ofbox->firstat line 12 inexample.cis reported to be a potential null pointer dereferencing. The output lists two more read vulnerabilities and one write vulnerability.Once an alarm has been reported for the access to an address, the possibly invalid pointer is assumed to be valid to prevent the generation of redundant alarms for this address. For instance, the memory access at line 13 is repeated at line 16 of

example.c, but it is not reported again as a memory vulnerability.- The third part starts with

Unproved additional alarms:and reports vulnerabilities inside the program's expressions. These expressions appear in the analysis's transfer functions. Because a transfer function may be called several times, these alarms may be repeated and may include some alarms of the second part above. In our example, no additional alarms are reported - The final part, starting with

Proved n/m regular alarms, gives the ratio of memory accesses proved safe over the total number of memory accesses, as well as the number of solved assertions

The regular alarm reported at line 12 of example.c is a false alarm, since the zeros_buffer function should always be called with a non-null argument. We can specify that by amending our type specification example.typedc. To do so, we replace the pointer star * by a plus + (which signifies non-null pointer) in the declaration of zeros_buffer as follows:

region buffer = ∃ len : int. (char[len])

struct message {

struct message* next;

buffer* buffer;

};

struct message_box {

int length;

struct message* first;

};

void zeros_buffer(struct message_box+ box);example-nn-ptr.typedc: refined type specification for example.c,

asserting that the function argument is not null.

Running the analysis again, we obtain the following output, where we can see that the memory accesses at lines 12 is now reported to be safe.

$ frama_c_codex -codex \

> -codex-use-type-domain -codex-type-file example-nn-ptr.typedc \

> example.c -main zeros_buffer -machdep gcc_x86_32 \

> -codex-exp-dump -codex-output-prefix v1-

[kernel] Parsing example.c (with preprocessing)

[Codex_config] Setting pointer size to 32

...

$ diff -d --unified=1 \

> --label naive v0-zeros_buffer.cdump \

> --label nn-ptr v1-zeros_buffer.cdump

--- naive

+++ nn-ptr

@@ -1,3 +1,3 @@

example.c:12.26-36: `box->first' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

-example.c:12.26-29: `box' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message_box*)

+example.c:12.26-29: `box' -> ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message_box*)

example.c:13.28-33: `first' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

@@ -20,3 +20,2 @@

Unproved regular alarms:

-example.c:12: Memory_access(box->first, read) {true;false}

example.c:19: Memory_access(current->buffer, read) {true;false}

@@ -25,4 +24,4 @@

Unproved additional alarms:

-Proved 1/5 regular alarms

-Unproved 4 regular alarms and 0 additional alarms.

+Proved 2/5 regular alarms

+Unproved 3 regular alarms and 0 additional alarms.

Solved 0/0 user assertions, proved 0

[1]The other accesses are still unproved because the memory layout has a stronger invariant than the one given by the new specification. We provide in Specification using Dependent Types the full process of proving the spatial memory safety for zeros_buffer by refining the specification of the memory layout even further.

First example in binary

We can also run our analysis on an executable binary file (which has all addresses resolved). To illustrate this analysis on our running example, we add the following main function to example.c in order to obtain an executable file example_full.c.

#include <stddef.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include "example.c"

int main(void) {

// Allocates the message box

struct message_box *box = malloc(sizeof(struct message_box));

box->length = 20;

box->first = NULL;

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

struct message *lst = malloc(sizeof(struct message));

lst->buffer = malloc(sizeof(char) * box->length);

lst->next = box->first;

box->first = lst;

}

// Fills the content of message box with zeros

zeros_buffer(box);

return 0;

}example_full.c: adds main function to example.c.

We then compile with the following command to generate an executable example.exe.

$ gcc -O0 -o example.exe -m32 -fno-stack-protector example_full.c

...The compilation is done using gcc with the following options:

-O0limits compiler optimizations in order to keep the executable close to the original program;-m32compiles the program for 32-bits architecture, which is the only one supported currently by our analysis. Note that, on a 64-bit platform, this requires gcc-mutlilib;-fno-stack-protectorremoves stack protection against stack writing overflow to easily compute the addresses on stack.

We can now run binsec_codex on the generated executable, using the same type specification file example.typedc:

$ binsec_codex -codex \

> -codex-type-file example.typedc \

> example.exe -entrypoint zeros_buffer

...

### Alarms ###

== _none_ ==

-alarm count-,-alarm- invalid_load_access,0,1,[0x000011da]

-alarm count-,ptr_arith,26,4,[0x000011a0 0x000011c0 0x000011c6 0x000011e2]

-total alarm count-,5

Analysis time: <dummy>

Total alarms: 5

...

[1]Same as for frama_c_codex we use a -codex flag to activate codex and -codex-type-file example.typedc to specify the type signatures. With binsec_codex though, we pass the executable example.exe and specify its entrypoint with -entrypoint zeros_buffer.

The output is quite verbose, we have hidden most of it under ellipses ..., since the most important part is the final summary. The part above ### Alarms ### is a full journal of the operations done by the binary analysis. Starting with ### Alarms ###, codex reports the vulnerabilities found. For instance, the instruction at address 0x000011da attempts an invalid read in the memory (similar to a null pointer dereferencing in C). To obtain the mnemonic of an instruction at some address, you could use objdump as explained below. The next alarm, ptr_arith, points out that a pointer arithmetic operation may return an invalid pointer. This is an unnecessary test done by the analysis because the code may not use this address, but it is useful to prevent wrong memory accesses.

When interpreting the output of the binary analysis, it is useful to decompile the executable in order to obtain the instructions at each address. This may be obtained by calling objdump on the program example.exe as follows:

$ objdump -d example.exe

...

0000118d <zeros_buffer>:

118d: 55 push %ebp

118e: 89 e5 mov %esp,%ebp

1190: 83 ec 10 sub $0x10,%esp

1193: e8 04 01 00 00 call 129c <__x86.get_pc_thunk.ax>

1198: 05 40 2e 00 00 add $0x2e40,%eax

119d: 8b 45 08 mov 0x8(%ebp),%eax

11a0: 8b 40 04 mov 0x4(%eax),%eax

11a3: 89 45 f4 mov %eax,-0xc(%ebp)

11a6: 8b 45 f4 mov -0xc(%ebp),%eax

11a9: 89 45 fc mov %eax,-0x4(%ebp)

11ac: 8b 45 08 mov 0x8(%ebp),%eax

11af: 8b 00 mov (%eax),%eax

11b1: 89 45 f0 mov %eax,-0x10(%ebp)

11b4: c7 45 f8 00 00 00 00 movl $0x0,-0x8(%ebp)

11bb: eb 12 jmp 11cf <zeros_buffer+0x42>

11bd: 8b 45 fc mov -0x4(%ebp),%eax

11c0: 8b 50 04 mov 0x4(%eax),%edx

11c3: 8b 45 f8 mov -0x8(%ebp),%eax

11c6: 01 d0 add %edx,%eax

11c8: c6 00 00 movb $0x0,(%eax)

11cb: 83 45 f8 01 addl $0x1,-0x8(%ebp)

11cf: 8b 45 f8 mov -0x8(%ebp),%eax

11d2: 3b 45 f0 cmp -0x10(%ebp),%eax

11d5: 7c e6 jl 11bd <zeros_buffer+0x30>

11d7: 8b 45 fc mov -0x4(%ebp),%eax

11da: 8b 00 mov (%eax),%eax

11dc: 89 45 fc mov %eax,-0x4(%ebp)

11df: 8b 45 fc mov -0x4(%ebp),%eax

11e2: 3b 45 f4 cmp -0xc(%ebp),%eax

11e5: 75 cd jne 11b4 <zeros_buffer+0x27>

11e7: 90 nop

11e8: 90 nop

11e9: c9 leave

11ea: 31 c0 xor %eax,%eax

11ec: 31 d2 xor %edx,%edx

11ee: c3 ret

...C Analysis Interface

In this section, we give an overview of the C analyzer's interface, i.e., the options of the analysis and the output it produces. The command line to call the analysis has the following form:

$ frama_c_codex -codex [-options] input_code.cOptions overview

Frama-C-codex has many command line options. An global list of these with short documentation can be found by running

$ frama_c_codex -codex-h

...

***** LIST OF AVAILABLE OPTIONS:

-codex when on (off by default), perform static analysis using

Frama-C/Codex. (opposite option is -no-codex)

...We present here the most useful ones:

-codex-use-type-domainselects our analysis that employs the domains based on types (we used it in all our examples until now).-codex-type-file FILE.typedcfixesFILE.typedcas the type specification file. It is a text file that contains the type declaration and signatures of the analyzed function using our extended type system. By convention, the extension of this file is.typedc.-codex-use-loop-domaintriggers the usage of a specific abstract domain, called induction variable analysis domain, which allows a precision gain when analyzing loops with inductive invariants.-codex-debug Nactivates the levelNof debug messages (0 is less verbose than 3).-focusingincludes the points-to predicate domain from [Nicole, 2022], which keeps track of the content of the memory during some analysis steps in order to increase the precision.-codex-serialize-cache, used in combination with-focusing, activates the join and widen operations in the points-to memory domain from [Nicole, 2022]; this increases precision, but also may degrade slightly the time performance or may produce some crashes.-codex-use-weak-typesenables the usage of “weak types” for the dynamically allocated values not yet initialized. This permit to infer the type of the allocated value semantically during the analysis of the initialization code, rather than syntactically using the type used at the allocation point.-main funsetfunas entry point of the analysis starting with the specification of this function. The functions called by the entry point are analyzed in an interprocedural way, i.e., their specification is used to create a summary and this summary is used by the analysis at each call point. This behaviour is disabled for functions specified to be inline (see Specifying Functions)-codex-html-dumpoutputs analysis result in a filefuncname.htmlfor an graphical representation of our analysis that details the computed abstract states at each point of the analyzed functions. For our example, this generates the following output: (full screen view) It also generates a more completefuncname.webapp.htmlwhich shows more information such as the full codex log and has more interactive features: (full screen view)

Output overview

Here we describe in more detail the dump file generated by Codex:

$ cat v0-zeros_buffer.cdump

example.c:12.26-36: `box->first' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

example.c:12.26-29: `box' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message_box*)

example.c:13.28-33: `first' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

example.c:15.15-26: `box->length' -> [--..--]

example.c:15.15-18: `box' -> ([1..0xFFFFFFFB] : struct message_box*)

example.c:18.20-30: `i < length' -> {0; 1}

example.c:18.20-21: `i' -> [0..0x7FFFFFFF]

example.c:18.24-30: `length' -> [--..--]

example.c:19.6-21: `current->buffer + i' -> [0..0x7FFFFFFE] or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : buffer[{0}].[0..0x7FFFFFFE]*)

example.c:19.6-21: `current->buffer' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : buffer*)

example.c:19.6-13: `current' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

example.c:19.22-23: `i' -> [0..0x7FFFFFFE]

example.c:18.32-35: `i + 1' -> [1..0x7FFFFFFF]

example.c:18.32-33: `i' -> [0..0x7FFFFFFE]

example.c:21.14-27: `current->next' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

example.c:21.14-21: `current' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

example.c:22.11-27: `current != first' -> {0; 1}

example.c:22.11-18: `current' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

example.c:22.22-27: `first' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

Unproved regular alarms:

example.c:12: Memory_access(box->first, read) {true;false}

example.c:19: Memory_access(current->buffer, read) {true;false}

example.c:19: Memory_access(*(current->buffer + i), write) {true;false}

example.c:21: Memory_access(current->next, read) {true;false}

Unproved additional alarms:

Proved 1/5 regular alarms

Unproved 4 regular alarms and 0 additional alarms.

Solved 0/0 user assertions, proved 0Abstract state

Our analysis first outputs the abstract states computed at each program point. We provide a semantic to this output by illustrating it on the output produced for the running example of the first section.

For instance, the abstract state computed for line 12 of the file example.c is given below. It states that the value stored by the field first at address given by box is either 0 or a value in the interval [1..0xFFFFFFFF] (the interval domain is used to abstract sets of numerical values). In addition to the interval of values, the type of box->first is reported to be a pointer to a struct message.

$ cat v0-zeros_buffer.cdump

...

example.c:12.26-36: `box->first' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

...

example.c:19.6-21: `current->buffer + i' -> [0..0x7FFFFFFE] or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : buffer[{0}].[0..0x7FFFFFFE]*)

...

example.c:19.22-23: `i' -> [0..0x7FFFFFFE]

...

example.c:22.11-27: `current != first' -> {0; 1}

...For the variables of numeric type, like i in example.c, the abstract value computed at line 19 is a 32-bits integer value, strictly less than length, so the computed interval is [0..0x7FFFFFFE] (1 less than the maximum 32-bit int value).

The more complex expression at line 19, current->buffer + i, is associated with the abstract value denoting the interval [0..0x7FFFFFFE] (when current->buffer is 0) or a value in the interval [1..0xFFFFFFFF] with type buffer[{0}].[0..0x7FFFFFFE]*. This type is a bit of a mouthful, so lets break it up:

- The final

*means it is a pointer - The

buffer[{0}]means it points inside abufferregion (recall we declaredbufferin the type specification fileexample.typedc) - The interval

[0..0x7FFFFFFE]describes the distance from the start of the region

Finally, the value of the test current != first on line 22 is either 0 or 1.

Reported alarms

The following parts of the output start with Unproved regular alarms. It concerns the potential vulnerabilities detected. The location of a reported vulnerability is given by the line in the source code and the columns of the memory access expression in this line. In the analysis of C code, two types of alarms are reported:

Regular alarms: mostly related to memory vulnerabilities or arithmetic errors. Once re- ported, these vulnerabilities are assumed to be false in the remainder of the analysis in order to avoid redundant alarms.

Memory_access(addr, read)signals that an attempt to read the memory ataddrmay be invalid because the pointeraddrmay be invalid.Memory_access(addr, write)signals that an attempt to write in the memory ataddrmay be invalid because the pointeraddrmay be invalid.Division_by_zerosignals that a division may use a zero divider.

Additional alarms: these are related to vulnerabilities found inside the transfer functions and can be generated multiple times for the same reason.

s -> load_param_nonptrindicates that an attempt to read the memory in statementsmay be an invalid pointer, usually because the pointer reads out of bounds.s -> store_param_nonptrindicates that an attempt to write in the memory in statementsmay be an invalid pointer, usually because the pointer writes out of bounds.s -> array_offset_accessindicates that an attempt to access the memory in statementsin some operations using arrays may be invalid.s -> serializeindicates that a join (or widen) operation tried to join (respectively widen) two abstract pointers of different types.s -> weak-type-useindicates that a recently allocated pointer whose type is not yet known is potentially used to access the memory.s -> typing_storeindicates that the type of a value may be incorrect for the following reasons:- the type of the value written in memory may be wrong;

- the type of the parameter given does not correspond to the pre-condition of a function summary;

- the returned value of a function does not have the correct type.

s -> free-on-null-addressindicates that a potentially null pointer was deallocated by statements.Return -> weak-type-leakindicates that the type of a recently allocated pointer is not known. This happens at the exit point of a function, when the analysis detects that a pointer was not written in the memory, neither returned from the function, thus leading to a memory leak.Return -> incompatible-return-typesignals that the type of the returned value does not correspond to the function profile in the specification. I.E. returning a value when the specified return type is void; or not returning a value for a non-void return type.

Binary Analysis Interface

In this section, we give an overview of the interface of the binary analysis: the options given in the command line and the meaning of the output produced. The analysis is called with the following line:

$ binsec_codex -codex [-options] input_code.exeOptions overview

The binary analysis may be tuned using the following command line options, some of them being shared with the C code analysis:

-codex-type-file FILE.typecfixesFILE.typecas input specification file; by convention, the extension of this file is.typedc.-codex-use-loop-domaintriggers the usage of a specific abstract domain, called induction variable analysis domain, which allows a precision gain when analyzing loops with inductive invariants.-codex-debug-level nactivates the level n of debug messages (0 is less verbose than 3).-no-focusingremoves the points-to predicate domain from [Nicole, 2022], which keeps track of the content of the memory during few analysis steps which decreases precision.-codex-serialize-cache, used in combination with-focusing, activates the join and widen operations in the points-to memory domain from [Nicole, 2022]; this increases precision, but also may degrade slightly the time performance or may produce some crashes.-codex-use-weak-typesenables the usage of “weak types” for the dynamically allocated values not yet initialized. This permit to infer the type of the allocated value semantically during the analysis of the initialization code, rather than syntactically using the type used at the allocation point.-hooks HOOKSallows us to stub some function calls or statements (given by their address) in the analysis. For instance:-hooks \ 0x0255d4=stop, \ iniTabTrans=stop, \ 0x025598=stop, \ 0x100055=skip_to(0x10005f), \ 0x0242d7=nop, \ 0x02558f=return_unknown(int)

This indicates to the analysis to stop the exploration beyond instructions

0x0255d4and0x025598, as well as when reaching a call to functioniniTabTrans. The hookskip_tostates that the analysis shall skip statements from line0x100055to line0x10005e. The hookreturn_unknown(int)states that the statement at line0x02558fis replaced by a store of a random value of int type in registereax. As for hooknop, it works as a way to skip to the next address.-config fnamesetsfnameas input configuration file; by convention, the extension of this file is .ini, in which the above options can be grouped instead being passed directly in the command line. Such configuration files may be used by several command lines.-codex-output-html fname.htmloutputs the analysis result in HTML format. Just like C, it generates two files: a basic overviewfname.html: (full screen view)And a more interactive webapp

result_webapp.html: TODO why isn't this namefname.webapp.htmllike inFrama-C? (full screen view)

Output overview

The binary analysis outputs a list of alarms of the following kinds:

invalid_load_access addrsindicates that an attempt to read the memory in instructions at addressesaddrsis possibly invalid because the pointer used is possibly null.invalid_store_access addrsindicates that an attempt to write in the memory in instructions at addressesaddrsis possibly invalid because the pointer used is possibly null.load_param_nonptr addrsindicates that an attempt to read the memory is invalid because the pointer is out of boundsstore_param_nonptr addrsindicates that an attempt to write in the memory is invalid because the pointer is out of bounds.array_offset_access addrsindicates that an attempt to do some operation using arrays was invalid.serialize addrsindicates that a join or widen operation tried to join respectively widen two abstract pointers of different types.weak-type-use addrsindicates that a recently allocated pointer whose type is not yet known is used to access the memory.typing_store addrsindicates that the type of a value is incorrect. This corresponds to a write of a value of wrong type or to a return value of wrong type.free-on-null-address addrsindicates that a possibly null pointer is deallocated.weak-type-leak addrsindicates that the type of a recently allocated pointer is not known. This happens at the exit point of a function, when the analysis detects that a pointer was not written in the memory, neither returned from the function, thus leading to a memory leak.incompatible-return-type addrssignals that the returned value does not correspond to the function profile given in the specification file.

Specification using Dependent Types

Our analysis does not need to modify the input programs with annotations. To specify the layout of the memory for which the memory vulnerabilities are avoided, the user provides a specification file. In this section, we present the specification language used by our analysis. This presentation is done gradually, starting with the automatic generation of a rough specification from the types used in the program (using cproto) and ending with a refined specification including most of the constructs of the specification language.

The full concrete syntax of our specification language is given in Type_parse_tree.

Automatic generation from C programs

The concrete syntax of our specification language is based on the C syntax for type and function declarations. This helps to easily generate a first specification using cproto, a tool available in any GNU based distribution.

For instance, to call cproto on example.c, we use the following command:

$ cproto -E 0 -f 3 -n -q -T -o example-cproto.typedc example.cThe command produces the following output stored in the file example-cproto.typedc (specified by the option -o above):

$ cat example-cproto.typedc

/* example.c */

struct message {

struct message *next;

char *buffer;

};

struct message_box {

int length;

struct message *first;

};

void zeros_buffer(struct message_box *box);As mentionned in the first example specification (example.typedc), in Codex types, the * is used to denote a pointer, but not a pointer to an array. To do so, one must specify that buffer points to char[n], and not to char. Since n is unknown, it must be quantified existentially (in a new named type):

$ cat example.typedc

region buffer = ∃ len : int. (char[len])

struct message {

...

buffer* buffer;

};

struct message_box {

int length;

struct message* first;

};

void zeros_buffer(struct message_box* box);

...Defining type and region names

Built-in C types (int, char, long, float, int32_t, uint8_t, void...). are predefined and can be used as in C. Their size depends on the selected architecture (32 or 64-bit, see Parse_ctypes.init). char will always have a size of one byte. We also have an integer type (distinct from int) and explicitly sized word1, word2, word4 and word8 types.

Type aliases

One can define simple type aliases using the type name = def; syntax, similar to C's typedef def name;, it provides an alias name for def. The following declare a new alias for char, and to 32-bit types, my_int and foo.

type char_alias = char; type my_int = char[4]; // Array of 4 bytes type foo = char[4];

Memory regions

Similarly, one can define new memory regions with region name = def;. As a basic rule of thumb, you can only have pointers to base types (int, char, etc) or to a defined memory region.

Our type system is nominal, so two regions with different names are considered distinct and may not alias. For example:

region my_int2 = char[4]; region bar = char[4]; type baz = bar;

Here, although my_int2 and bar have the same definition, aliasing them is forbidden. However, aliasing between bar and baz is allowed, since baz is just a shorthand notation for bar.

The C-like struct syntax we have used in example.typedc) is actually syntactic sugar for region name = def; statements. We could rewrite the example specification as:

TODO cram test

region buffer = ∃ len : int. (char[len])

// Here "struct message" is the new region name

region struct message = struct {

struct message* next;

buffer* buffer;

};

// The struct prefix is optional, I can also simply name thie struct "message_box"

region message_box = struct {

int length;

struct message* first;

};

void zeros_buffer(message_box* box);Note that, for compatibility with C, we allow names to be identifiers prefixed with struct or enum. We could just as well have named our region "message" instead of "struct message":

region message = struct {

message* next;

buffer* buffer;

};After the equal sign, the struct type expression defines a record type with the same syntax as in C, although the type definitions support our full type system.

Our region construct is equivalent to a C type definition typedef without the attribute may_alias available for GNU C. Therefore, the equality test fails between values of different types even if their value domain is the same, i.e., between value of type bar and my_int2 defined above. Like in C, our construct prevents writing at an address a value typed by a different type name than the address. This semantics of memory stores in presence of aliasing is called weak update in [Simmonnet et al. 2024].

Refined Types

Our type system supports refinement types, i.e. type endowed with simple predicates.

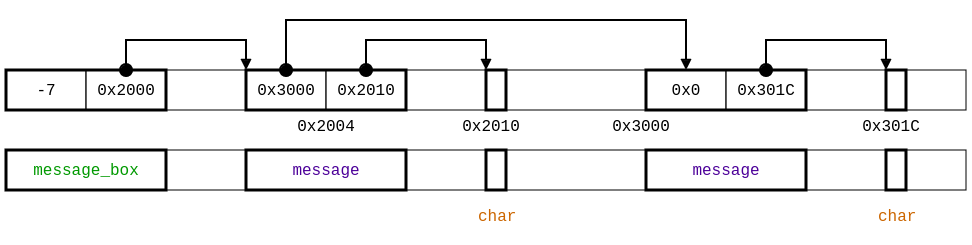

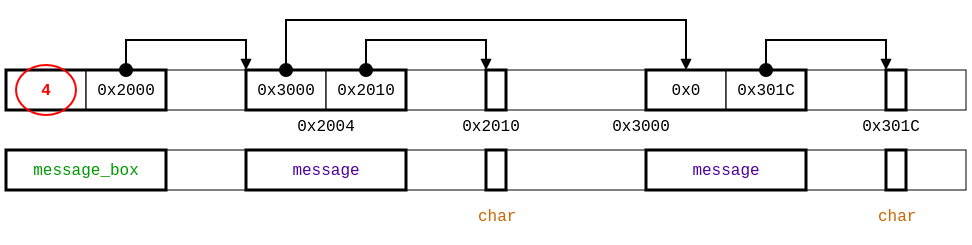

Consider the example specification example-nn-ptr.typedc, we can illustrate the possible memory layout is provided as follows: (the first line illustrates a possible content for the memory while the second line gives the type of each memory region).

This specification of the memory layout allows negative values for the length field of a message_box and a buffer in message containing a single char. Our analysis reports potential vulnerabilities while accessing current->buffer at line 19 in read and write:

$ cat v1-zeros_buffer.cdump

...

example.c:19: Memory_access(current->buffer, read) {true;false}

example.c:19: Memory_access(*(current->buffer + i), write) {true;false}

...This vulnerability does not appear if the length field is positive. To specify this, we may use a refined type expression int with self >= 0. Similarly, the vulnerability for memory read may be removed if the pointer current is not null, which may be expressed using the refined type "struct message* with self != 0". We have already seen in the introduction a simpler syntax for non-null pointers: replacing the * with a +. Similarly, we can mark the buffer field in the struct message is also non-null.

Moreover, to control the aliasing of the length field inside the struct message_box by a variable typed by an int*, we use the region integer of 4-byte, which is different from int. The new specification is then:

region buffer = ∃ len : integer with self >= 0. (char[len])

struct message {

struct message* next;

buffer+ buffer;

};

struct message_box {

integer with self >= 0 length;

struct message+ first;

};

void zeros_buffer(struct message_box+ box);

example-refined.typedc: type specification for example.c

using refinement types for length, along with a representation of the memory layout.

$ frama_c_codex -codex \

> -codex-use-type-domain -codex-type-file example-refined.typedc \

> example.c -main zeros_buffer -machdep gcc_x86_32 \

> -codex-exp-dump -codex-output-prefix v2-

[kernel] Parsing example.c (with preprocessing)

[Codex_config] Setting pointer size to 32

...

$ diff -d --unified=1 \

> --label nn-ptr v1-zeros_buffer.cdump \

> --label refined v2-zeros_buffer.cdump

--- nn-ptr

+++ refined

@@ -1,5 +1,5 @@

-example.c:12.26-36: `box->first' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

+example.c:12.26-36: `box->first' -> ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

example.c:12.26-29: `box' -> ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message_box*)

-example.c:13.28-33: `first' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

-example.c:15.15-26: `box->length' -> [--..--]

+example.c:13.28-33: `first' -> ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

+example.c:15.15-26: `box->length' -> [0..0x7FFFFFFF]

example.c:15.15-18: `box' -> ([1..0xFFFFFFFB] : struct message_box*)

@@ -7,5 +7,5 @@

example.c:18.20-21: `i' -> [0..0x7FFFFFFF]

-example.c:18.24-30: `length' -> [--..--]

-example.c:19.6-21: `current->buffer + i' -> [0..0x7FFFFFFE] or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : buffer[{0}].[0..0x7FFFFFFE]*)

-example.c:19.6-21: `current->buffer' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : buffer*)

+example.c:18.24-30: `length' -> [0..0x7FFFFFFF]

+example.c:19.6-21: `current->buffer + i' -> ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : buffer[{0}].[0..0x7FFFFFFE]*)

+example.c:19.6-21: `current->buffer' -> ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : buffer*)

example.c:19.6-13: `current' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

@@ -18,10 +18,9 @@

example.c:22.11-18: `current' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

-example.c:22.22-27: `first' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

+example.c:22.22-27: `first' -> ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

Unproved regular alarms:

example.c:19: Memory_access(current->buffer, read) {true;false}

-example.c:19: Memory_access(*(current->buffer + i), write) {true;false}

example.c:21: Memory_access(current->next, read) {true;false}

Unproved additional alarms:

-Proved 2/5 regular alarms

-Unproved 3 regular alarms and 0 additional alarms.

+Proved 3/5 regular alarms

+Unproved 2 regular alarms and 0 additional alarms.

Solved 0/0 user assertions, proved 0

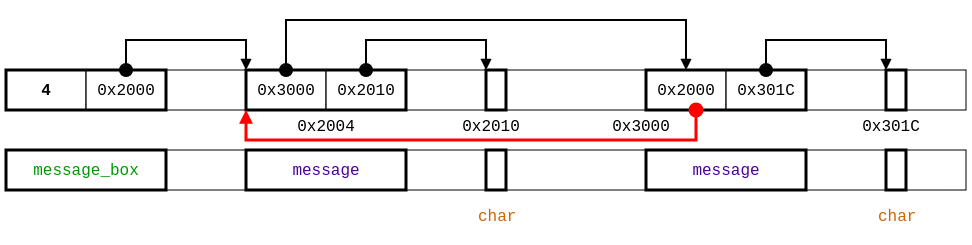

[1]Notice that we still have alarms for memory access to current->next. Looking at the code, it appears the message list starting at first is supposed to be circular. Thus current->next will never be null. To specify this property, we set next field to be of type non null pointer, which over-approximates the circular list shape by a lasso shape (since the number of memory addresses is finite). Furthermore, we observe that the code employs both buffer and first fields as non null pointers.

region buffer = ∃ len : integer with self >= 0. (char[len])

struct message {

struct message+ next;

buffer+ buffer;

};

struct message_box {

integer with self >= 0 length;

struct message+ first;

};

void zeros_buffer(struct message_box+ box);

example-lasso.typedc: type specification for example.c

specifying the message list as a lasso shape.

Running with this new specification, we can see that Codex has proven all memory accesses safe:

$ frama_c_codex -codex \

> -codex-use-type-domain -codex-type-file example-lasso.typedc \

> example.c -main zeros_buffer -machdep gcc_x86_32 \

> -codex-exp-dump -codex-output-prefix v3-

[kernel] Parsing example.c (with preprocessing)

[Codex_config] Setting pointer size to 32

...

$ diff -d --unified=1 \

> --label refined v2-zeros_buffer.cdump \

> --label lasso v3-zeros_buffer.cdump

--- refined

+++ lasso

@@ -10,3 +10,3 @@

example.c:19.6-21: `current->buffer' -> ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : buffer*)

-example.c:19.6-13: `current' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

+example.c:19.6-13: `current' -> ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

example.c:19.22-23: `i' -> [0..0x7FFFFFFE]

@@ -14,13 +14,11 @@

example.c:18.32-33: `i' -> [0..0x7FFFFFFE]

-example.c:21.14-27: `current->next' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

-example.c:21.14-21: `current' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

+example.c:21.14-27: `current->next' -> ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

+example.c:21.14-21: `current' -> ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

example.c:22.11-27: `current != first' -> {0; 1}

-example.c:22.11-18: `current' -> {0} or ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

+example.c:22.11-18: `current' -> ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

example.c:22.22-27: `first' -> ([1..0xFFFFFFFF] : struct message*)

Unproved regular alarms:

-example.c:19: Memory_access(current->buffer, read) {true;false}

-example.c:21: Memory_access(current->next, read) {true;false}

Unproved additional alarms:

-Proved 3/5 regular alarms

-Unproved 2 regular alarms and 0 additional alarms.

+Proved 5/5 regular alarms

+Unproved 0 regular alarms and 0 additional alarms.

Solved 0/0 user assertions, proved 0

[1]Existential types

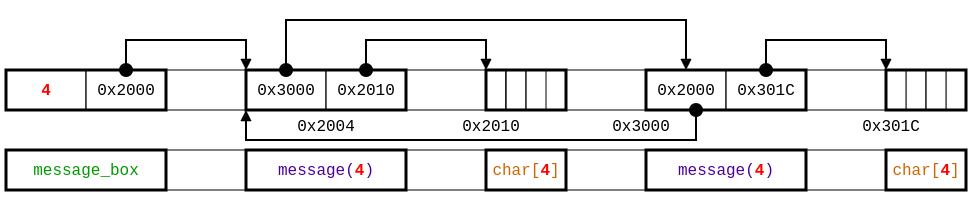

For now, we have mostly glossed over the existential type at the start of our specification. It is required to state that the pointed region is an array, and not some small value.

The existential type expression ∃ x : T . U introduces a local variable x (of type T) in a type U. In our example, the variable len, of positive integer value is introduced as the size of the allocated memory region at the address buffer. Therefore, buffers may contain multiple character not just one and, moreover, each buffer may have a different length. The resulting specification and an allowed memory layout are given by Figure 5. Therefore, the existential types allow to express local invariants in a type expression, i.e., invariants between the fields of the same memory region.

Parameterized types

TODO no remaining alarms

The specification in above does not remove the false alarm reported for array out of bound access because the function zeros_buffer expects that all the buffers in a message box have the same length given by the field length in message_box. This is not a local invariant for a memory region because the value stored in some memory region (field length in a region typed by message_box) is related with a value (length of a buffer) in another region of a different type (e.g., message). To exchange this information between memory regions, we specify that the type message is parameterized by a value of type integer and we use existential and refined type expressions to pass the value of the field length as actual parameter of the first pointer to a message(mlen) type. The specification is then:

struct message(len) {

struct message(len)+ next;

char[len]+ buffer;

};

∃ mlen:integer with self > 0.

struct message_box {

integer with self = mlen length;

struct message(mlen)+ first;

};

void zeros_buffer(struct message_box+ box)

example-lasso.typedc: type specification for example.c

using parameters.

$ frama_c_codex -codex \

> -codex-use-type-domain -codex-type-file example-lasso.typedc \

> example.c -main zeros_buffer -machdep gcc_x86_32 \

> -codex-exp-dump -codex-output-prefix v5-

[kernel] Parsing example.c (with preprocessing)

[Codex_config] Setting pointer size to 32

...

$ diff -d --unified=1 \

> --label lasso v3-zeros_buffer.cdump \

> --label param v5-zeros_buffer.cdumpSpecifying Functions

Our specification language follows the C language syntax for function declaration. To this, we add several advanced features:

- Annotation

inlineforces the analyzer to inline the function code rather than applying an inter-procedural analysis; if the function is recursive, the analysis will fail. - Annotation

puresignifies that the function does only “in frame” operations on memory, like reading, writing on addresses at local variables or writing in a recently allocated region. In other words, it indicates that the abstract memory is unchanged. This allows the analyzer to be more precise in inter-procedural analysis of function calls. Existential types may be used to express invariants between function’s arguments and result. For instance, the following specification states that

RandTreereturns a complete binary tree of heightn:∃ h:int with self > 0. (node(h)+ RandTree( (int with self = h) n));Functions may receive as arguments pointers to functions:

list+ map_list_int(list + l, ([int] -> int)+ f);Our type system as three different syntaxes to represent anonymous functions:

int(*)(int, char) // C like syntax - only allows pointers [int, char] -> int // More legible ocaml-inspired alternative int <- (int, char) // Reversed version